I was sixteen the summer of 1981, and active in my church youth group. As in the rest of my life, in youth group, I occupied the shadowy fringes of the social scene. I studied and admired those who shone in the spotlight of popularity and confidence, but I watched from a distance. I saw myself as a plain, but smart girl, the "best friend" but never the heroine in the fairy tale. Disinterested boys confirmed this viewpoint. I decided that I was destined to a life of spinsterhood, probably living in some remote land, ministering to needy, destitute people, probably as a doctor.

And then, I met Rita.

I hailed from Seattle, Washington, and had never met anyone from Oklahoma before I met Rita. I was quiet, kept to myself, followed rules, listened a lot. Rita and I were part of a group of teenagers who were on a short-term missions trip. Most of the others at our training session were heading to the Philippines, but Rita and I and five other girls were going to Tahiti.

I remember my first personal encounter with Rita in the Los Angeles International Airport. I remember her teasing me about my accent, which I found uproariously funny because everyone

knows that girls from Seattle don't have an accent. She thought I sounded like a

Valley Girl , an accusation which I denied. I then had her perform the alphabet and laughed out loud at her rendition--she managed to turn each letter into a two or three syllable word. I had never heard such a thing, even when I watched Hee-Haw on television with my dad.

And then, we became friends. We spent almost three weeks living together in a borrowed house on a hillside overlooking Papeete, Tahiti. She photographed lizards on the walls and a giant cockroach in the hallway and we giggled about the overflowing toilet and learned that one cannot dispose of tampons in the toilets in Tahiti. Who knew? We did our best to talk to the Tahitian teens who belonged to the church we worked with. I supplied my limited working knowledge of French (I'd taken a year in school) and what she lacked in language skills, she made up for in enthusiasm. We were quite a team.

She matter-of-factly declared that I was the Beauty and she was the Brains and I was so taken aback that I didn't argue. I'd always been the Brains in any friendship I'd had in my real life back home in Seattle. But I began to believe her when the Tahitian boys started gazing in my direction and flirting with me in a language I didn't entirely understand. This was entirely unprecedented.

I began to notice one handsome Tahitian boy always seemed to be at my elbow. His name was Jean-Claude and he was almost exactly my age. Tahitians greet one another with a kiss on each cheek and when he'd greet me, he'd linger just a moment longer than necessary and murmur into my ear. This turn of events shocked me. The boys at home never noticed me at all and now a tall, dark, handsome boy was pausing with his lips near my ear?

Our final night in paradise, a dinner was held in our honor. I cradled a Tahitian child in my lap, sad beyond words, sad beyond explanation. When we left that small home with its tile floor and buzzing mosquitoes, I sobbed in the darkness as we walked along the path to our car. I wanted to stay forever.

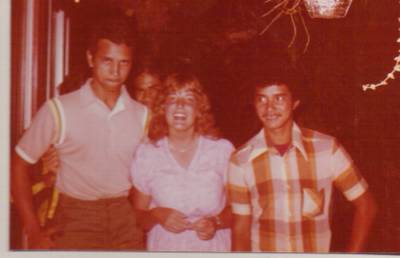

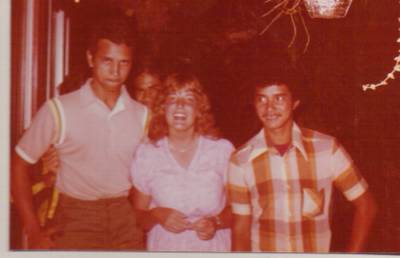

Our last night, right before I cried my eyes out:

I was distraught to leave this place and this new me behind, the Beauty I had never been before, the one the boys followed with their eyes. I didn't want to abandon this dream and return to my life where my hair never quite stayed feathered and no one noticed whether I entered a room. I knew I'd step foot on my high school campus and turn back into the Brain, the Teacher's Pet, the Smart Girl, the Blob.

Sure enough, that's what happened. But every day I ran the last block towards my mailbox to check for mail. More often than not, I found a letter from Rita or less frequently, a letter from Jean-Claude. I wrote impassioned, funny letters back to both of them. Those letters were tangible reminders of who I was in that other place.

After I saw myself though stranger's eyes, I never did see myself the same way again. I began to believe I was funny and maybe, sometimes, a tiny bit pretty. I realized that the small world of my high school (396 kids in my graduating class) was smaller than I ever knew. The whole wide world beckoned to me, and in that other world, I wasn't just a Smart Girl with a 3.96 grade point average.

I stayed in touch with Rita for many years--we even ended up attending different colleges in the same town. She phoned me a few years ago and we tried to catch up on the news after the years of silence. She has twin boys, too, and a daughter. She teaches English in a high school.

I don't suppose I ever told her how much her friendship really meant to me. Her viewpoint, her vision of me, her confidence in me changed how I saw myself. Friends like that don't come along every day.

Jean-Claude and I exchanged passionate letters for a year or two (all in French since his English was worse than my French), until he announced his intention to come to the United States to marry me. I admit that I completely freaked out and hastily wrote him back a letter declaring I did not love him. I was seventeen, maybe eighteen. What did I know of love? Three weeks in Tahiti when you are sixteen do not mean anything when you are talking about love and eternity. Plus, my dad would have killed me if a Tahitian boy suddenly showed up on our doorstep declaring his love for me.

But I thought of Jean-Claude today, because today he turns 40. I like to imagine him on that black sand beach where we once spent an afternoon playing a game that was a mix between Tag and Capture the Flag, using a flip-flop. I can picture him playing with his children with their shiny black hair and lumimous brown eyes. I hope he's living happily ever after.

I know I am. And there is just a teeny, tiny part inside me that pipes up every once in a while and says, "What would have happened if . . . " And I say "Hush, you silly girl!" and then I yell at my kids to be quiet because they are driving me crazy and is it bedtime

yet?